It was the colonial era in India, sometime in the 1940s. Our hero, Sudhangshu, was a bright young advocate in his early thirties, living in Calcutta in the eastern parts of India. He travelled often across Bengal and Bihar to plead cases in district courts. Those trips had made him comfortable with long roads, unfamiliar places, and the kind of silence that settled over the countryside after dusk. He liked travelling alone, though he was always reluctant, in a quiet corner of his heart, to leave behind his young and beautiful wife.

This time he had to travel to a rural part of Bihar to appear in the district court. It was a civil matter, a property dispute in a large joint family, messy with claims and counterclaims, and it promised good fees if he handled it well. The plan was simple. He would reach his destination on Sunday evening by train, stay overnight somewhere, possibly in a Dak Bungalow that he would arrange through the stationmaster, and then take a bus on Monday morning to the court. After finishing his matter, he would return to Calcutta by the afternoon train.

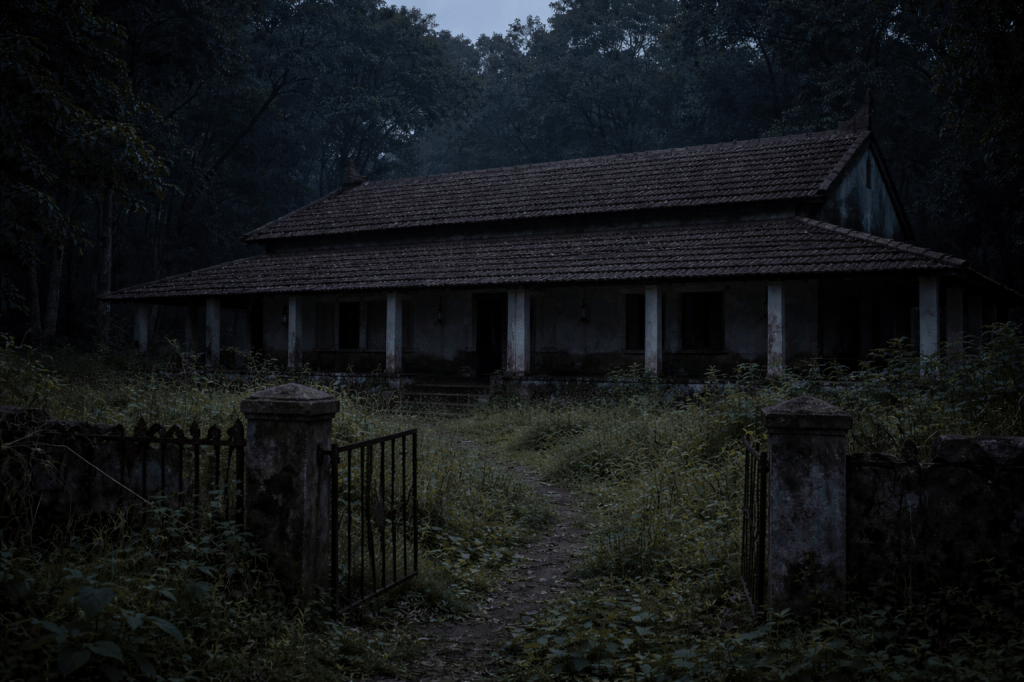

A British era Dak Bungalow in rural India was typically a sturdy colonial single-storey rest house, brick built with a sloping tiled roof and a deep verandah. These bungalows were set up every fifteen to twenty kilometres for the mail route, meant to offer a bed for the night, nothing more. There was usually a caretaker, the chowkidar, who lived on the premises and kept the lamps, water, and locks in working order.

Sudhangshu reached the station around 4:30 in the afternoon. The sun was still up, bright and confident, and the small station looked straight out of a painted picture in that light. But Sudhangshu was oblivious to its quaint beauty and went straight to the stationmaster’s room, and asked where he could stay for the night. The stationmaster’s table was neat, with papers stacked in stiff little piles. An inkpot sat open, but the nib looked dry.

The stationmaster looked up from his papers and said, “Dak Bungalow is there, but I do not know whether the chowkidar will be there today. He has gone for a wedding invitation in the next district. Sometimes he returns late, sometimes not.” He said it like a plain fact, but he did not hold Sudhangshu’s eyes while saying it. For a moment his glance went past Sudhangshu, briefly, towards the window, as if checking how much daylight was left.

Sudhangshu frowned. “Then what?”

“Try your luck,” the stationmaster said, already going back to his papers. “If he is there, he will open. If not, you will have to come back or go to the bazaar side ten kilometres from here and find a place.”

Sudhangshu decided to take a chance. The idea of spending the night at the station, or travelling ten kilometres to the bazaar in search of doubtful accommodation, did not excite him. He signed his name in a worn register and took the customary note from the stationmaster for access to the Dak Bungalow. It was a short note, folded twice, the paper slightly soft at the edges. He slipped it into his pocket and stepped outside.

Now he needed a ride, bullock cart or horse cart, anything that would carry him before the light faded. He waited. Ten frustrating minutes passed before a single bullock cart appeared, moving slowly as if it had all the time in the world. Sudhangshu approached eagerly and asked to be dropped at the Dak Bungalow. The stationmaster had said it was about five kilometres from the station, but the bazaar, the only other option, lay ten kilometres away in the opposite direction.

The driver hesitated. “Sahib… Dak Bungalow?” he repeated slowly. Then he looked up at the sky, squinting as if he was measuring the light rather than the distance. His lips moved soundlessly for a moment, as if he was counting something under his breath.

“Ok, Sahib… I will take you there,” he said at last, “but you have to give me four anna more, and I will drop you a little away from the main gate.”

“Why away?” Sudhangshu demanded, the suitcases in his hand getting heavy by the minute.

The driver shrugged without meeting his eyes. “It is better, Sahib.” He said quickly.

Sudhangshu felt irritation rise. It was robbery in daylight. He looked around and for the first time he noticed how quiet the station road had become. He knew there might not be another cart for a long while, it would soon be dark and he did not like lingering at the small station. He gave in with a sigh and climbed in.

The cart creaked forward. The bullocks’ hooves struck the mud track with a dull rhythm. The road ran through open fields and thin trees. Now and then the wind carried the smell of damp leaves and cow dung. As they moved farther from the station, another smell came and went, faint and metallic, like old iron left in rain. Sudhangshu noticed it once, but dismissed it as nothing.

He tried to keep his mind on the case. He needed to be sharp tomorrow. He was ambitious. A favourable verdict would mean good fees and better references. Still, as the afternoon light started slipping away, he realised how empty the road was. No cyclists, no children, no tea stalls. Even the birds seemed quieter.

After a while, he saw it: the Dak Bungalow. It did not announce itself. It simply appeared at a bend in the road, sitting alone in an open patch, its tiled roof dark against the lowering sun. The verandah looked like a long black tape running around the building, and the windows, though shut, gave the impression of someone watching from behind. Behind it, the forest line began abruptly, dense and untrimmed, as if the trees had grown there in a hurry and then stopped.

In the daytime the white single-storey building would look plain, almost official. But now in the soft red glow of the setting sun, it seemed to sit a little apart from the world, as if the land around it had learnt to keep a respectful distance. The nearer the cart came, the quieter the world seemed to become, as if the place demanded silence.

Sudhangshu leaned forward. “That is it. Go on.”

The driver pulled the reins.

“Sahib, you have to get down here.”

Sudhangshu stared. “What nonsense? The bungalow is still ahead. I have suitcases. And I paid you more.”

The driver’s hands were shaking. He did not look towards the bungalow. “Sahib, please. Here only.”

Something in his voice was not stubbornness. It was fear, plain and unornamented. Sudhangshu argued for a minute, then stopped. He had seen this kind of fear before in villagers, fear that did not answer questions.

Cursing under his breath, he got down. The driver had dropped him about five hundred metres from the gate. Sudhangshu paid him.

The driver snatched the money as if he wanted it out of his hand quickly, whipped the bullocks, turned the cart around, and left at a speed that did not match the tired animals. Within moments, the cart was already far, retreating from the bungalow.

Sudhangshu watched it disappear. The evening air had changed. It was cooler, damp, and the faint wet iron smell was stronger near the trees.

He turned and started walking, briefcase in one hand and suitcase in the other. It was not a long distance, but it felt oddly stretched. The road seemed narrower. The shadows under the trees looked dense and motionless, as if something sat inside them and did not bother to hide.

When he reached the main gate, he noticed it was rusted and slightly tilted. The compound looked neglected at the edges. Weeds grew where a path should have been, and the grass had a flattened look. The bungalow itself looked maintained and functional, but there were no lamps, no smoke, no hint that anyone actually lived there. Near the verandah steps, the air carried a distinct smell—metallic and damp—like wet iron kept in a closed room.

He found himself hoping, almost against reason, that the chowkidar would be there. The thought of turning back and walking all the way to the station, with the light failing, was far from exciting.

Sudhangshu called out loudly, “Chowkidar! Chowkidar!”

A middle-aged man appeared almost at once, as if he had been standing just inside the darkness waiting for that call. He wore a cotton dhoti and a faded kurta, the cloth washed thin at the elbows, with a red gamcha thrown over one shoulder. His feet were in worn out slippers, and his hair was neatly oiled and combed back, though a few grey strands escaped at the temples. He had a small moustache and a face that was otherwise ordinary—sun-darkened, lined in the way village faces are—except for the eyes. The eyes were sharp and wakeful, fixed on Sudhangshu with an alertness that did not relax, even when he smiled.

“Ji, Sahib… most welcome, Sahib,” he said, taking the luggage with quick, practised hands. “I believe you are looking to rest here for the night.”

“You are here?” Sudhangshu blurted. “The stationmaster said you had gone to a wedding.”

The chowkidar smiled. “No, Sahib,” he said. “I am here.”

Sudhangshu fished for the stationmaster’s note inside his pocket, but the chowkidar did not even glance at it. He only shifted the luggage as if it weighed nothing and said, in the same calm tone, “Come inside, Sahib.”

Sudhangshu did not know what to make of that, but he was tired and he did not like appearing foolish. He followed the chowkidar inside.

The chowkidar led him into a large living room that seemed to serve as both sitting and dining space. There was a sofa, some chairs and a centre table, arranged with a kind of stiff neatness. The whitewashed walls had turned yellowish with age, the plaster wearing off in places and leaving odd, uneven patches like old bruises. The walls were mostly bare except for a portrait of a stern British officer, his eyes fixed forward with such hard anger that Sudhangshu felt, for a moment, as if he had annoyed the man by intruding into his space.

Kerosene lamps had already been lit and placed neatly. Their flames were steady but small, and the light seemed to stop short of the corners, leaving them too deep and too still. The floor was swept clean, yet it had the faint stickiness of old humidity. The room smelled of brick and limewash warmed and cooled over decades, with something underneath—damp cloth and old kerosene that never quite went away. Somewhere inside the house, a slow creak sounded, as if a wooden beam was settling under a burden it had carried for too long.

And behind it all, through the walls and shut windows, Sudhangshu could feel the forest—not as sound, but as a thick silence pressing in from the back of the bungalow, patient and close.

The chowkidar showed him into one of the two bedrooms. It was basic but functional, clean in a way that felt dutiful rather than lived in. Apart from the bed there was a cupboard, a writing desk, a chair, and a large punkha hanging over the bed. The punkha’s cloth looked heavy with age, its edges slightly frayed, as if it had been pulled for years in rooms like this. The rope disappeared through a hole near the ceiling, vanishing into the darkness above, and for a moment Sudhangshu wondered where it led to.

“Should I pull the punkha for you, Sahib?” the chowkidar asked.

“Not required,” Sudhangshu replied. “Instead, show me the bathroom so I can freshen up.”

Like a dutiful servant, the chowkidar led him out onto the verandah and towards the bathroom. The verandah ran long along the front of the bungalow, its roof low and its pillars thick, holding the last warmth of the day in some places and turning strangely cold in others. The kerosene lamp that the chowkidar was holding threw a weak yellow circle ahead of them, and beyond that circle the verandah seemed to fall away into shadow.

As they walked, Sudhangshu caught that smell again—metallic, damp—stronger here, close to the bricks, as though it had soaked into them long ago. The air was so still that even their footsteps sounded louder than they should have.

Sudhangshu noticed, without knowing why, that the chowkidar kept to one side of the passage, avoiding the other. It was probably nothing, yet it felt a little odd.

“Who all live here?” Sudhangshu asked, partly out of politeness, partly because he disliked the thought of being alone in such a place.

“Only me, Sahib,” the chowkidar said quickly. “But you do not worry. I can cook better than any khansamah. I will serve you chicken curry and rice for dinner. I will be in the kitchen. You can call me anytime if you need anything.”

“I have tea in my flask and I want to work on my case notes,” Sudhangshu said. “I do not need anything. Call me for dinner around 8:30.”

“Ji, Sahib,” the chowkidar replied.

After freshening up and having a steaming cup of tea from his flask, Sudhangshu settled at the writing desk in the bedroom. He laid out his notes and soon became absorbed. Outside, dusk fell properly. The forest behind the bungalow swallowed the last light. The kerosene lamps burned on, their flames steady, but now and then trembling as if a draught passed though no window was open.

At some point, without lifting his head, Sudhangshu heard a faint scrape from outside his room, as if something metal had been shifted and then carefully steadied. He paused, listened for a moment, then went back to his notes.

It must have been an hour when his concentration was broken.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib,” said the chowkidar from behind him.

Sudhangshu did not turn. He glanced at his watch. “It’s only 7:20. Call me at 8:30.”

“Ok, Sahib,” the chowkidar said, and left.

Sudhangshu went back to reading. Ten minutes later he heard the soft approach again. This time, before the voice, he heard that sound again—a faint scrape, as if a tray’s edge had brushed the wall.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib.”

Sudhangshu frowned. “Not now, chowkidar. Please do not disturb me. I am concentrating on my work.”

“Sorry, Sahib,” came the reply, and the footsteps withdrew.

Sudhangshu tried to shake it off. He read on, making notes. He found a decision that fit his argument and felt a brief surge of satisfaction. He dipped his pen again.

Then the lamp flame shivered. The room seemed to dim for a second, then steady. And this time, the voice came closer—too close, as if the speaker had not stopped at the doorway.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib.”

Sudhangshu spun around, irritation ready on his tongue.

A chowkidar stood in the doorway holding a dinner tray.

Only the chowkidar had no head.

For a moment Sudhangshu’s mind refused to accept what his eyes were showing. The body stood upright, steady, in the calm posture of a servant doing his duty, as if nothing was wrong and nothing had ever been wrong. The neck stump looked impossibly clean, as if cut with a single sure stroke. There was no wild mess, no jerking movement. Blood did not spray. It oozed slowly—thick and dark—falling onto the floor with soft, careful drops. Even the blood seemed to have learnt to keep quiet in this house.

On the tray lay the chowkidar’s head.

His eyes were open.

His lips were moving.

And when the voice spoke again, it did not seem to come only from that mouth. It felt as if it was inside the room itself, as if the bungalow had learnt the sentence long ago and was now saying it through him.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib.”

Sudhangshu could not breathe. The smell hit him then, the same smell that has been following him around—warm wet iron, like fresh blood meeting old brick!

The kerosene flame trembled, and the shadows on the wall jumped in small quick movements, as if the room itself had flinched.

The head blinked once, slowly, as if tired but determined. The lips shaped the words again, politely, obediently, almost anxious, as if the sentence mattered more than anything else.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib.”

Sudhangshu’s chair scraped the floor as he stood up. His body moved before his mind could decide. He ran—straight past the apparition that stood patiently at the doorway, waiting to complete its duty.

Sudhangshu ran out of the room, out of the bungalow, into the compound, and onto the road, leaving luggage and papers behind. His feet pounded the earth. Branches scratched his arms. He stumbled, got up, and kept running.

Behind him, always at the same distance, neither rushed nor delayed, he heard a sound that followed his steps—the faint scrape of something carried, the soft clink of a tray being kept level with great care.

And the voice, calm and punctual, came through the darkness like a duty that refused to die.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib.”

He ran harder.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib.”

The words did not grow loud. That was the worst part. They stayed steady, as if spoken by someone walking just behind his shoulder, patient and polite.

“I have brought you dinner, Sahib.”

Sudhangshu’s lungs burned. His throat tasted of dust. He did not know how long he ran. The road turned, the trees opened, the night spun. Finally, his legs failed him. The world tilted. Darkness rose.

When he opened his eyes, it was morning. Sunlight lay across a village lane. A group of villagers stood around him, staring. Someone offered him water.

Sudhangshu tried to speak. His mouth was dry. “Where am I?”

“You were lying here before dawn,” a man said. “Unconscious. Clothes torn. Face grey like ash.”

Sudhangshu swallowed. “The Dak Bungalow… where is it?”

“Did you spend the night at the Dak Bungalow?” asked an old man, the confusion plain in his face. “But the chowkidar has not returned. How did you…?” He stopped mid-sentence, as if a sudden understanding had struck him. His voice dropped further. “What happened there, babu? Did you see anything?”

By the time Sudhangshu finished his tale, the little circle around him had grown quieter. No one interrupted. No one even cleared their throat. A few of the villagers had begun muttering prayers under their breath, and one man kept making a small protective gesture with his fingers, again and again, as if he could ward something off by doing that.

When Sudhangshu fell silent, the old man looked away for a moment, towards the road that led back to the forest, as though he did not want to meet anyone’s eyes.

Then he spoke, very softly. “Listen, babu,” he said. “An incident happened there fifty years ago. A chowkidar delayed his master’s dinner by a few minutes. The British sahib became furious. He dragged the man to the verandah and cut off his head for that offence.”

The old man paused, then added, quieter, “The blood went into the floor. Into the brick. Into the smell of the place.”

Sudhangshu stared at him.

“Since then,” the old man continued, “on some nights the chowkidar is seen there. He comes to correct his ‘crime’. He serves dinner on time.”

Another villager muttered, “On time… always on time.”

The old man nodded once. “Only he does not carry chicken curry and rice anymore.” He lifted his hand as if showing the shape of it. “He carries a tray.”

No one moved. Even the younger men kept their eyes down.

“And on the tray,” the old man said, “neatly placed like a dish… is his own head. Eyes open. Lips working. As if he is still afraid of being late again.”

Sudhangshu felt his throat tighten.

The old man went on, “But the sightings are rare. Sometimes years pass and nothing happens. But few times in living memory, travellers were found at dawn on the road like you—clothes torn, eyes wild—refusing to go anywhere near that bungalow again.”

He fell silent.

No one spoke. No one asked questions. It was as if the village had learnt, long ago, that some stories were safest when they were told quickly and then allowed to end.

Leave a reply to Bipasha Cancel reply